Summit Exercises and Training LLC (SummitET®) has developed a virtual communications training solution specifically for Nuclear Power Plants and offsite response organizations. Training and exercise requirements have become a challenge since the response to COVID has...

SummitET Experts to Discuss Radiation Communications Strategies at National Radiological Emergency Preparedness Conference (NREP)

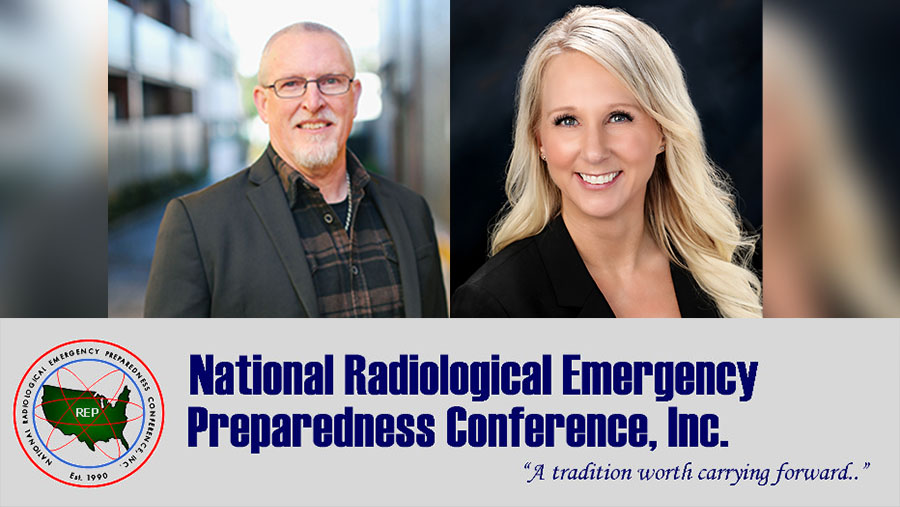

Summit Exercises and Training LLC (SummitET®) experts will be presenting at the 33rd annual National Radiological Emergency Preparedness Conference (NREP) in Indianapolis, Indiana from April 3 to 6, 2023.

The mission of NREP is “to provide a professional forum for individuals involved with the Offsite Radiological Emergency Preparedness programs to gather in the spirit of continuous self-improvement to share program experiences, develop solutions to common challenges, and create innovative planning, exercising, and training methodologies.”

SummitET offers multi-agency radiological preparedness exercises, trainings, and workshops for emergency planners and field personnel, led by our team of Strategic Communications experts, Certified Health Physicists, and Radiation Safety experts.

Join our expert session during the 2023 NREP Conference:

“Public Information to Crisis Management: Spokesperson Strategy and Practice for Radiation Emergencies”

Authored By: Mark Basnight, Holly Hardin, Angela Leek and Steve Sugarman

Unprepared radiation spokespersons increase the risk to their organization’s brand and credibility as well as their personal reputation as effective leaders. They need to be prepared to comment on a wide range of topics and to provide clarifications of untrue statements. Whether your agency needs to share information regarding a news event, has an internal story to tell or is trying to publicize a new product or service, radiation spokesperson training can be helpful in getting your story out. Using interactive and participatory methods, senior leaders and radiation spokespersons will engage in practice to enhance development of stakeholder maps, key messages, talking points, and strategies for engaging multiple audiences using science-based methods and industry best practices.

Visit Our Booth

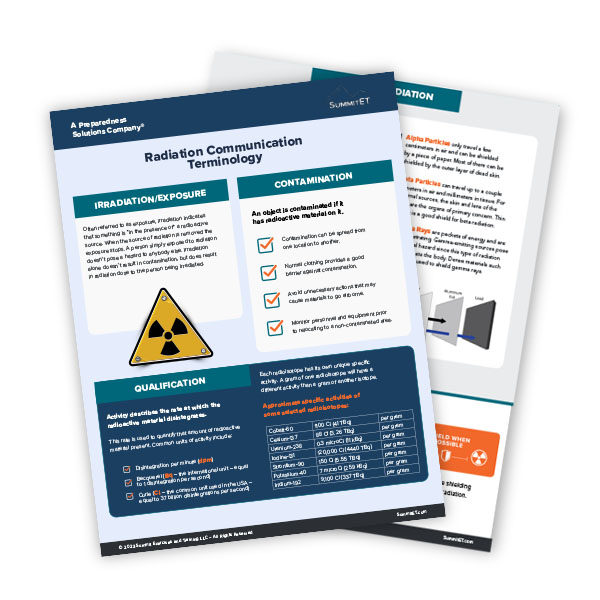

Visit us at Booth #18 to receive hard copies of our Radiation Communications tools.

Prescripted Radiation Emergency Messages

Simple Radiation Communication Strategy for Radiation Emergencies

Meet with Our Experts

Steve Sugarman

VP of Operations & Corporate Health Physicist

Angela Leek

Director of Radiological Solutions and Regulatory Affairs

Radiation Communications Resources

SummitET News

SummitET Develops Virtual Communications Training Solutions for Power Plants

SummitET Announces Social Responsibility Initiative

Summit Exercises and Training LLC (SummitET®)’s strategy is to build a sustainable future ensuring that the mission and vision of the company is tied to core values that are dedicated to making a positive contribution to society. SummitET’s emphasis on social...

SummitET International Alliance Ranked Third Globally for Tenth Consecutive Year

Summit Exercises and Training LLC (SummitET®)'s international alliance of independent accounting and professional services firms, TAG Alliances®, has been recognized by Accountancy Age as one of the top three accounting alliances in the world. This is the tenth...